Andrew Beck

CATALOGUE ESSAY | VISIONS, Auckland | JULY 2020

Processes of subversion, conversion and inversion collide in the photographic practice of Andrew Beck, an artist who deploys the vicissitudes of light as formal and conceptual agent. Engaging with a technique popularised by the early twentieth century avant-garde, Beck’s photograms are hatched from carefully constructed source material, seaming the present with stitches from the past in a way that points to the aesthetic inertia of contemporary culture.

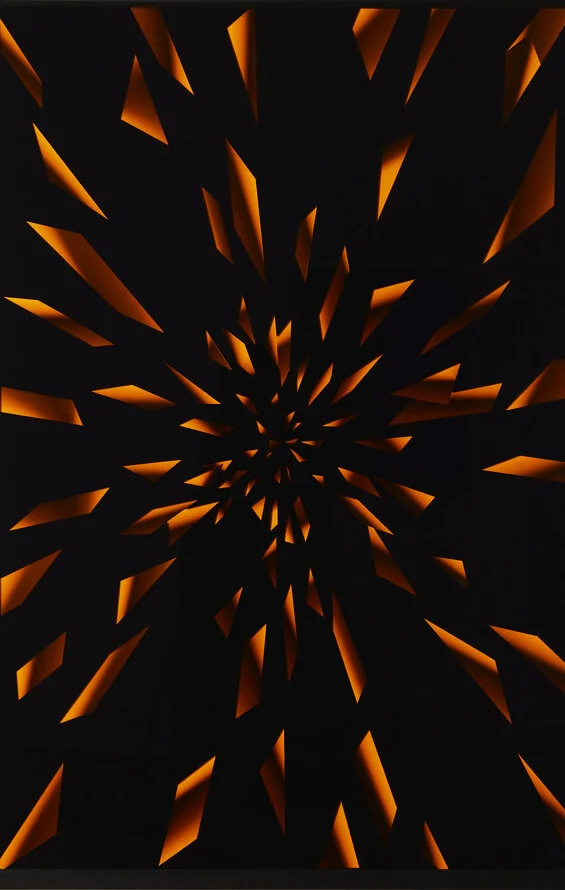

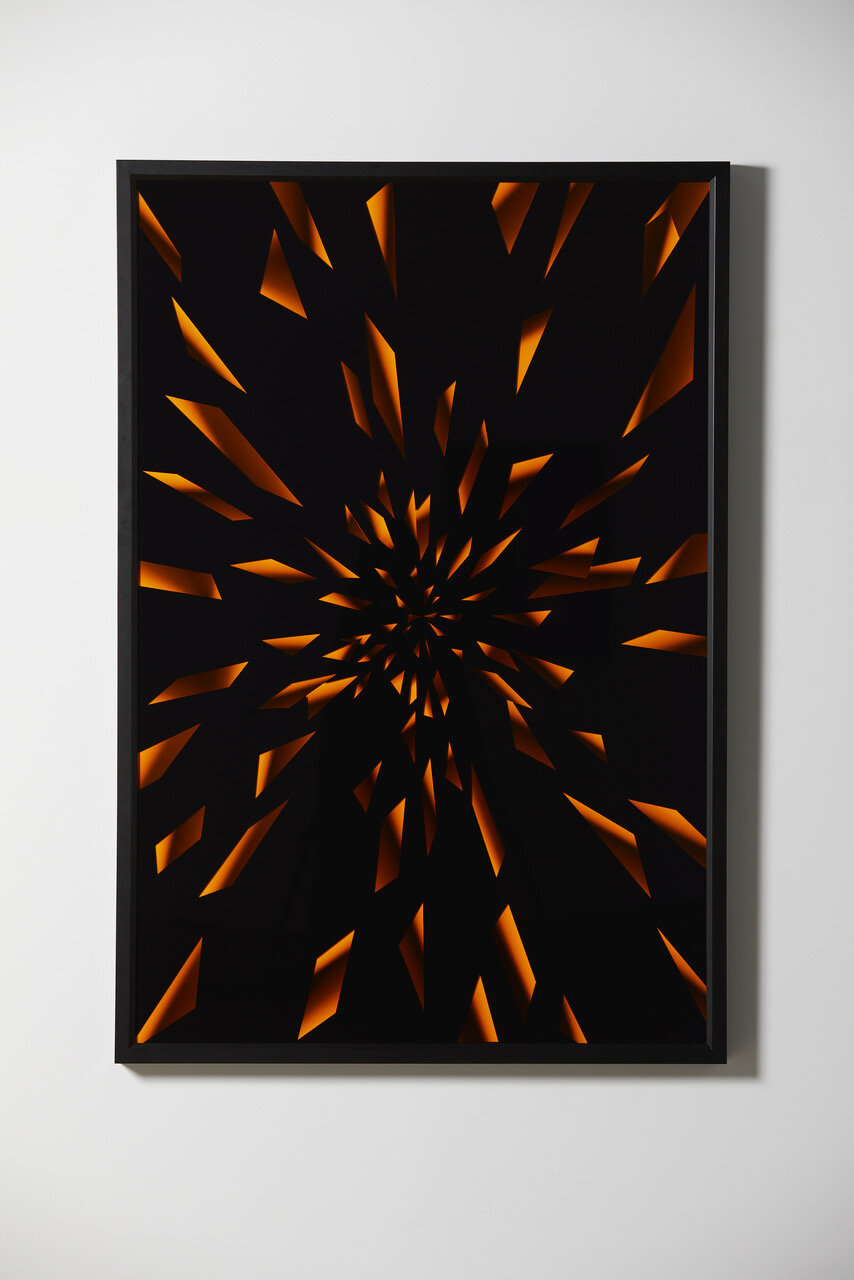

Intersecting photography, sculpture and installation, Beck’s sleek hard-edged geometries and graduated tonalities subvert modern valorisations of the artist’s hand by camouflaging the physical labour of their production. His complex methodology involves creating material stimuli before scanning them into the computer, making transparencies and physically processing them – some over a metre square – in the darkroom. They become analogue expressions of digitality, and the more layers and processes the image undergoes, the greater the mileage from its original representation. Here, Beck consciously invokes our current moment in postmodernity, a place of constant rehashing and the refurbishment of old, already-established cultural forms. Iris I, for example, depicts a constellation of yellow-tinged shapes; residues of an original composition that has been rebuilt into a new aesthetic architecture. There is a sci-fi accent here, as if we are piloting a spacecraft as it jumps to hyperspace or navigating through an onslaught of space debris. Unlike many other works by Beck, Iris I has a defined sense of depth as the tonal shards expand outwards from a faraway nucleus – fragments, perhaps, from a forgotten form, catapulting the viewer into a hypnotic, cyclonic spiral.

Examining the idea of a lost or ‘cancelled’ future, Beck filters his works through the theoretical lens of Mark Fisher, looking at the ways in which today’s retrofuturist aesthetics and narratives recycle mid-twentieth century visions of a future that never arrived. Breaking down boundaries between science fiction and cultural theory, Fisher suggests that we’re experiencing a cultural impasse or ‘hauntology’, to use Derrida’s neologism, besieged by that which no longer exists. Beck considers this ontological stance in his photograms, which literally enact cycles of reforming and reanimating; symptomatic indeed of a culture that finds appeal only in pre-established cultural modes. Through a hands-on methodology, his works embody the paradox of retrofuturism: that new technologies are subordinated to the repetition and looping of the past; the new parrots the old. They speak of early Internet aesthetics, cyberpunk and digital communications endemic to Beck’s childhood in the eighties and nineties – a time considered by many to be the endpoint for new aesthetics. The artist also siphons influence from meme culture and Vaporwave – a music microgenre involving sampling, splicing and looping eighties and nineties pop songs, elevator music, soundtracks and commercials – to explore the trend of nostalgia as a means of caching oneself in the safety of the familiar. Though this sense of retro-revivalism isn’t explicit, his photographs stir up strands from their own processual past as well as the personal past of their maker, reconstructing moments akin to the process of a painter or sculptor. And yet, although the works recall their early material forms, they’re divorced from inceptive context through the act of layering. Source materials come to exist only as glimmering spectres that never quite allow themselves to be revealed. Culturally, this reflects processes of deterritorialisation, to borrow from Deleuze, whereby social structures are severed from their territorial moorings.

While Liquid Shatter I brings us back to what we might read as conventionally photographic; part of the cognizable world, it is in fact an inversion of the photographic process, dispelling the mediator of the lens and creating what is essentially a negative. To make the work, Beck physically arranged droplets of water on a sheet of glass, in the dark, to try to replicate the composition of Iris I. As the liquid imitates the yellow geometric shards, a new form of mimicry unfolds; one in which the natural simulates the artificial. Water becomes allusion and illusion, with its dramatic shadow play and ornate metallic sheen incarnating the galactic, the alchemic and the technologic. Here again is a tacit salute to sci-fi, as if the jump to hyperspace in Iris I has transmuted into a glitchy 3D-rendering where light becomes something solid. The genetic code of Iris I has been reshuffled such that its indexical referents hang by a thread.

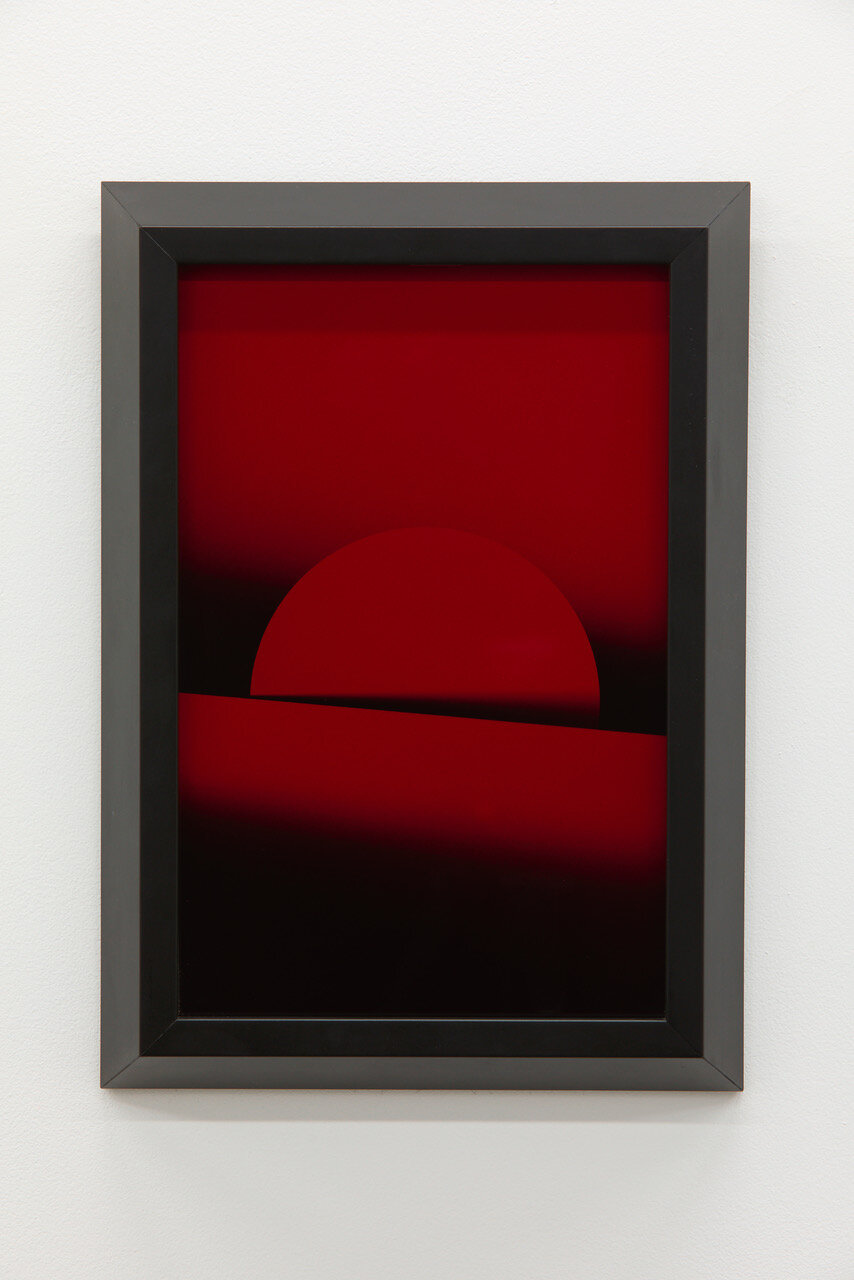

Beck’s works are both analogue and analogues, stirring together the decidedly handmade with notions of similitude to examine the nature of the photographic image in relation to reality and representation. Framed and wedged into the corner of the gallery, Apex I converses with a wall painting beside it, Apex I, visually connected via black triangular apexes. The physical object collides with its reproduction in an iterative rendition of Jean Baudrillard’s oft-cited philosophical prodding of postmodernity, which describes a virtual image regime of simulated reality that has no causal connection to a pre‐existing or knowable real. Indeed, while Beck’s images intersect abstraction, they are an index of real forms – signs of reality with no locatable referents. They loiter on the cusp of recognition, furnished by flickers of information that seem to conceal more than they reveal. In Iris, the artist has distilled the shape of an eye into a split-toned rhombus, conjuring a kind of geometric opticality. This work allusively points to diagrammatic representations of the nature of vision – where two triangles meet each other as an image is inverted inside the eye (before being re-inverted by the optic nerve). Beck’s schematic ‘eye’ visualises a new breed of perception, one where natural and technological anatomies are spliced together. It consciously summons Donna Haraway’s mobilisation of the cyborg metaphor to revoke ontological divisions between natural organisms and artificial machines, emblemising the hybridised, socially constructed and multiple identities of postmodern subjectivity. Beck’s Iris tells us that the eye is no longer the seat of the soul.

The chromatic personalities of these artworks further tap into systems of perception. All of Beck’s images are black and white, overlaid with a sheet of tinted glass; like a filter. Glass fascinates the artist on a material level, for its propensity to simultaneously transmit, absorb and reflect light. The glass veneers each photographic image, which is then overlaid with a sheet of non-reflective conservation glass. This has the effect of doubling the image at certain angles – a momentary diplopia that brings the trope of the iris back into sharp focus. Beck’s monochrome works enlist primary colours to probe how we register colour in the retina, translating painterly notions of yellow advancing, red receding and blue dwelling in the middle. An iridescent filter in Ocula I causes the colours to morph as the viewer moves around the image, firmly lodging vision as a haptic experience. Though smaller in size than the other photographs, Ocula I is a focal point of the show, tuning the primary colours much like the focal point of an eye. Its prismatic spectrum recalls the neon colour schemes of the eighties, looping back to the longitude of the past – to the lustrous possibilities of a stalled future. We are confronted, once again, with the quivering aura of a crystallised artefact.